Abstract

Almost all athletic endeavors require some form of speed, agility, and quickness to accomplish the sport’s tasks and enable the athlete to become superior over his opponents. Designing a routine that includes each of these facets into an athlete’s training program can be challenging. This is due to the understanding that each athlete is different and comes with different experience levels and learning skills. It is proper to use progressive exercises that start the novice athlete off with modalities and drills that enable him correctly grasp the methods and in turn let his motor learning skills adapt and comprehend them.

Starting athletes off in advanced drills to early will lead to sensory overload and cause them to take two steps backward through regression. This is why it is crucial to properly instruct athletes on the right mechanics for running, cutting and jumping prior to using modalities. Once adequate progression is implemented, coaches can bring in visual and auditory cues to take training to the next level and push their athletes farther. This paper will break down speed, agility, and quickness into separate training forms. Also, it will elaborate with detailed warm-ups, progression, exercises, and drills to effectively produce a superior performance enhancement program.

Speed

Speed is the accumulation of enhanced acceleration and velocity. This is vital for any athlete to become successful in his sport. Designing drills that help increase an athlete’s stride length and stride frequency are important. It helps him become faster and effectively produce more speed. “One way to increase stride length and frequency is to increase overall functional strength throughout the entire body” (Brown and Ferrigno, 2005).

An athlete can achieve functional strength through power movements like the deadlift, clean and press, and snatch exercises. Improved strength levels will allow athletes to produce greater amounts of force while at the same time decreasing the time spent in contact it with the ground” (Brown and Ferrigno, 2005). Many players involved in athletics fail to realize the potential that speed training has on developing their overall power and velocity that can carry over into their sport of play. The old montage that players are born fast and that speed cannot be developed is highly false. Research and experience have shown that speed development and power can be achieved through proper training with increasing progressions and modalities.

Before allowing an athlete to use any type of modality, it is best to instill in them the proper techniques and mechanics for speed improvement. “Proper mechanics allow the athlete to maximize the forces that the muscles are generating. This greatly improves the chances that an athlete will achieve the highest speed expected of him or her, given his or her genetic potential and training” (Brown and Ferrigno, 2005). Having proper posture, arm action, and leg action is imperative to becoming a faster athlete. Detailed below is a systematic approach for athletes to develop maximum acceleration and speed through a warm-up, supplemental speed work, resisted, assisted, and contrast assisted and resisted runs.

Warm-up

A proper warm-up is necessary to prepare the body for the exercises and modalities that are to follow. Also it is necessary to prevent any injuries from cold muscles. Exercise such as jogging and skipping can be beneficial to produce a mild sweat. This should last for 5-10 minutes in length.

Dynamic Stretch

Once the core-temperature is increased and the athlete has perspired mildly, dynamic stretching should be introduced. Dynamic stretching helps to lubricate the joints, stimulate the nervous system and increase range of motion (Brown and Ferrigno, 2005). Also, it helps prepare the athlete for the more demanding tasks ahead. Exercises that are useful include A-Skips, walking lunges, Tin Man and toe walking.

Resisted Sprinting drill: Weighted Vest

One of the best ways to add resistance to an athlete and increase their stride length is using the weighted vest. Here, an athlete will place a loaded vest over his shoulders to supply resistance. It is important to note that athletes should not be slowed down by more than 10%. This is because, as the resistance becomes greater, the ground dynamics begin to change. Weight from the vest should not be evaluated by the athlete’s body weight due to some being stronger and more powerful than others. The weighted vest will help the athlete develop explosive acceleration through consistent training. This is a great drill to begin a speed training program due to the athlete being fresh and able to handle the extra load that the vest brings. Have the athlete perform 3-5 sets of 35-yard sprints.

Assisted Sprinting Drill: Bungee Over-stride Drill

Athletes can increase their stride rate by using over-speed drills with the bungee. This drill compliments the exercise using the weighted vest. The athlete has primed their nervous system to function at a higher weight due to the load from the vest. Here, the first athlete will line up on the goal line with one end of the bungee attached around their waist while their partner lines up approximately twenty-two yards down the field with the other end of the out-stretched bungee attached around their waist. The second player standing twenty-two yards downfield will also want to take two large steps to their left to allow their partner to sprint to the right of them and use more force.

You will instruct athlete number one on the goal line to place both feet together and raise his heels of their ground. Now, you will instruct athlete number two who is downfield to sprint as fast as they can, while towing their partner, to the fifty-yard line at the blast of the whistle. Once the whistle is sounded, player one will take off as well, and allow the momentum of player two’s bungee pull to accelerate him past the fifty-yard line.

This drill can be administered directly after a resisted-sprint modality. It should be performed for four sets with the thirty-second break in between. One thing to consider while pairing up partners for the over-speed drill is to make sure they are around the same size. Otherwise, one smaller player might not be able to effectively build enough power to tow a larger athlete and therefore make the drill ineffective. This is also a great drill to provide coaching cues to both athletes where their mechanics and form can be practiced and perfected.

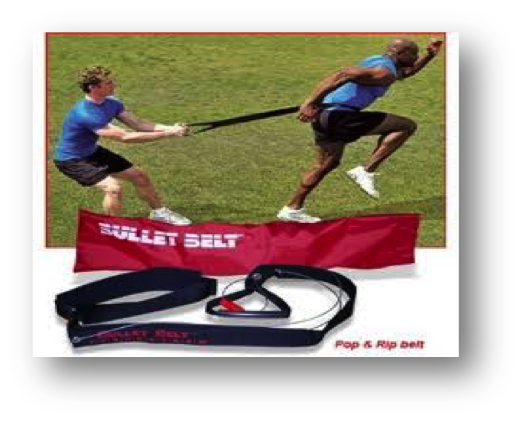

Contrast-Resisted Sprinting Drill: Bullet Belt Drill

Contrast-Resisted Sprinting Drill: Bullet Belt Drill

One great drill that will help with stride length and acceleration is the Bullet Belt trainer. The Bullet Belt is a modality that enables the runner to run with resistance for ten yards. It pulls his partner, and then allow to sprint freely from his partner by releasing the ripcord on his belt. Set up two cones ten yards downfield and another set thirty yards downfield. The runner will wrap a belt around his waist and buckle it secure and then stand on the goal line where his partner will stand behind him using a strap to apply resistance.

At the end of the sprinting athlete’s belt, facing behind him is a Velcro tail that will be used to add resistance to the sprint motion. The second athlete will place a strap with two other Velcro ends to the first athlete’s Velcro tail. Next, the athlete holding the secured strap will apply resistance to the first athlete by holding a handle. The first athlete will use a correct forward lean with elbows tight and sprint as fast as he can while towing his partner who is using resistance to hold him back to the first set of cones ten yards downfield. Once the sprinting athlete reaches the ten-yard mark, the second athlete will pull the ripcord and allow him to sprint past the thirty-yard marker.

Contrast Assisted Sprinting Drill: Downhill-to-Flat Contrast Speed Runs

This drill is used to maintain “supramaximal” speed for a short distance in the absence of assistance. (Brown and Ferrigno, 2005). During this drill, an athlete will start off about twenty yards behind the bottom of a hill and build up speed through the bottom of the hill where he will try to maintain that “supramaximal” speed as he transitions onto the flat ground for another ten to fifteen yards (Brown and Ferrigno, 2005). Contrast-assisted sprinting drills help increase top-end speed as well as stride rate. Instruct the athlete the keep his elbows tight and drive with the hips for four sets with fifteen second rest periods. This drill is great for athletes who need to work on their top-end speed through plays such as soccer, football, and basketball players.

Agility

Agility training enables the athlete to focus on quick movements that involve cutting, coordination, power, and acceleration. Designing a program that combines all of these abilities into a drill is what makes agility training so successful. The repetitious nature of agility drills helps involve neural adaptations that help the athlete get better over time (Halberg, 2001). Agility training is not natural to most athletes. Therefore coaches must start them off with basic movements and slowly incorporate ladders, hurdles, and plyometric boxes in order to keep the athlete improving. Listed below are progressive agility exercises that provide open and closed drills with ladders, hurdles, and cones. Athletes need to use the same warm-up and dynamic stretching drills outlined above to properly warm their muscles and prime their nervous system for the drills ahead.

Basic Biomotor Agility Drill: Carioca Exercise

A great basic exercise to help the athlete build neuromuscular adaptation to the sport they are playing is the Carioca drill. Here, the athlete will continuously transition their right and left legs in front and behind each other while twisting his hips. This drill helps the athlete to learn the basics of staying on the balls of their feet and keeping their knees bent. Have each player face one direction and Carioca in between twenty-yard cones for four sets. After the athlete can accomplish this drill with his head up, it would be beneficial to add in hurdles and ladders to keep the drill challenging.

Closed Drill: Ladders

Closed Drill: Ladders

A closed drill with the ladder is great to implement into an intermediate athlete’s program. It allows his motor learning skills to adapt and become more efficient with footwork. Dawes notes that the use of closed skills is appropriate to allow the desired motor behaviors to be learned and perfected (Dawes, 2008). The ladder drill is designed to force the athlete to learn how their feet should land and where through repetition. One great ladder drill is the “Two Foot Run Through.” In this drill, a player will jog through the ladder rungs by placing his right toe in first, directly followed by his left toe. This causes him to concentrate on fast, direct steps with lots of repetition.

Here, an athlete should practice with four sets consecutively, followed by a one-minute rest. Once he becomes more advanced with his footwork, you can decrease the work-to-rest ratio. Ladder drills are great for all athletic events. It forces the player to learn how is feet should react and work in quick scenarios.

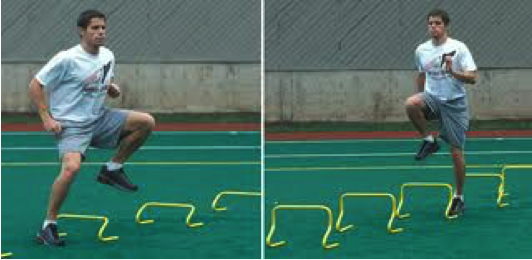

Closed Drill: Hurdles

Another great closed drill that helps train the athlete’s neuromuscular system is one in which he has to jump over hurdles. Line up six to eight hurdles linearly with one-foot distance in between. The hurdles are great agility tools by using the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) to help the nervous system recruit more fast-twitch muscles to enable a higher firing rate. By recruiting and activating more of these fast-twitch fibers, the athlete will have better force production; which will carry-over to quicker multi-directional cuts and turns.

Just like the ladder drill, there are numerous exercises that can be used with the hurdles. One that is great for teaching the athlete to stay on his toes is “Bunny Hops”. This drill has the athlete put both feet together and stay low with knees bent. Lacrosse and soccer players are appropriate for this drill due to the repetitive jumping and landing that occurs during games. Having the athlete perform three to four sets with one minute of exercise between each full round is sufficient to help him learn and recover properly.

Open Drill: Box Drill with Visual Cues

For the more advanced athlete who has developed and finely tuned the exercises above, the Open Box drill with visual cues is next in the progression. Line up four cones in a box shape with ten yards distance between each cone. Next, place one different colored cone directly in the middle of the box to act as the fifth cone. Instruct each athlete to shuffle around the cones facing inside the whole time. After two rounds, further, instruct the team to call-out the number that you are holding on your hand above your head. This forces them to keep their heads up as well as work on the peripheral vision to maneuver around the cones. This drill is a very advanced agility drill. An agility program should only include it once an athlete has shown great skill and confidence with the Assorted Biomotor Skills and Closed Drills.

Quickness

Quickness, fundamentally, is the foundation for being able to accelerate and build speed as well as having great agility. Also, quickness relies on immediate reactions through various movements that in essence is the first phase of speed. Quickness drills should emphasis fast reaction time training that further assists the neuromuscular system to adapt to rapid mechanisms. Having a fast reaction time is critical because it is shown to be a precursor of quickness (Brown and Ferrigno, 2005). Outlined in detail below are three quickness drills. That will progressively advance from reaction time training, plyometrics, and reaction drills with commands.

Reaction Time Training: Mirror Drills

Mirror Drills focus on lower-body reaction speed as well as quickness from point to point. Set up four cones in a box pattern five yards apart. Each athlete will start in the middle of their designated box, where one will be on offense and the other on defense. The goal for the defensive athlete is to “mirror” exactly what his offensive opponent is doing. The offensive opponent has to run to a cone by sprinting, backpedaling, or using and over-stride method with the intention of outmaneuvering his opponent. The defensive player will try to keep up and stay on point against his opposition. Run this drill for fifteen-second intervals with thirty seconds of rest in between. Each athlete will go two rounds of being offense and defense. A great coaching cue is to instruct each athlete on defense to keep their head up and lock eyes with their opponent’s chest.

Plyometrics: Jump Rope Skipping

Jump roping is one of the most basic forms of plyometric exercises, but also one of the most efficient. It helps increase lower body quickness and elastic strength by using the stretch-shortening cycle. Here, you can have an athlete perform 100 repetitions on a single-leg (right and left); then the same using both feet. As the athlete advances, auditory cues are useful to make the player change patterns and sequences. Start off with four sets of twenty-five reps and gradually advance them to one single set of 100 consecutive reps.

Reaction Drill with Command: Sprint and Back Pedal on Command

This drill helps the athlete to improve reaction time by recruiting the ability to change directions swiftly. Have the athlete start in a two-point stance. Each time the athlete hears the whistle, he will change movements between sprinting and backpedaling. This is a slightly advanced drill due to many novice athletes have a hard time transitioning between various movements on command. To make the drill even more advanced, the coach can add a shuffle, over-stride, or incorporate plyometrics into each movement. Perform four sets non-stop with a one-minute rest at the end.

References:

Brown, L. and Ferrigno, V. (2005). Training for Speed, Agility, and Quickness. Human Kinetics, 2ndEdition.

Dawes, Jay. (2008). Creating Open Agility Drills. National Strength and Conditioning Association, 30(5) 54-55.

Halberg, G. (2001). Relationships among Power, Acceleration, Maximum Speed, Programmed Agility, and Reactive Agility; TheNeural Fundamentals of Agility, Masters thesis. Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, MI.