Being in nature can help your body and mind heal and speed up the Covid-19 recovery process

In this article, you will learn about a study of n=2 female athletes’ recovery and returning to endurance training after covid-19 infection. You will also learn about the effects vaccinations may have on the athlete, and what to take into consideration when adjusting athletes’ training around the vaccinations. You will also learn what to monitor as you work with your athlete through this period. In addition, you will learn that there is no need to panic about detraining and that the re-gaining fitness is quicker than you think!

In February I wrote about how to get back to regular training after the initial Covid-19 infection. You can read it here. Just recovered from the initial phase and was leaning into research to learn more about how to safely return to training for Ironman.

I wish it had been smooth sailing. I was in for a challenge of patience.

As Covid-19 is still very much a new disease, with multifactorial effects on individuals, we do not know that much. Here, I will share what I have learned about the aftermath with two athletes, and what the limited research tells us. It is a battlefield requiring patience, self-compassion, and tons of grit to get through.

Covid-19 Recovery Experience of a Female Long Distance Triathlete In Her 40s

This athlete had the infection at the end of January. The infection was mild and she quickly recovered from headaches, congestion, and lethargy. By day 10 she was feeling great and walked on the treadmill for 15 mins. Those 15 mins were more for her mental health than anything else. She was feeling good enough to move her body, and she was anxious about losing the fitness she had worked so hard to gain.

She was monitoring her heart rate response with morning HR and HRV (Heart Rate Variability) daily. All good to go with low morning HR and high HRV. Her HR jumped up about 20 beats the day 2 post positive test but then quickly returned to the normal range of 50-60 bpm.

Day 11 she started with the Gradual Return To Sports guidelines by Eliot et al. (read the article here). She was walking, running, biking every day for 20-60 mins at <80% of Max HR. She felt fine and breezed through the program. This training load was a far cry from what she was used to pre-covid (10-15hrs per week).

On day 21 she completed the program. She was mentally and physically ready for more. Afterward, I believe, although she was feeling well, it all went too fast.

She then overdid it and did a 60 min easy bike ride in the morning followed by Valentine’s run with her hubby in the evening. Shit hit the fan. She was exhausted for days. Back to 15 mins walks and easy bikes.

For three weeks she struggled with headaches and extreme fatigue. Here’s what she said about the struggle.

Every time I tried to run at an easy, slow pace, my HR would increase to 150ish, which is around my Tempo (Z3) pace. an increase of 20-30 bpm while running easy Z1 pace / effort IS NOT normal. So I would drop down to walk and my HR would come down to 90s. i noticed my hr would also drop a lot slower than normally when i turned to walking. it was mostly the headaches and extreme fatigue, crashing mid-day that worried me.

A little increase in hr during workouts would be expected after a few weeks of inactivity due to de-conditioning, but we should not be looking at a big jump like 20-30 beats on a low effort level.

She decided to take a week really easy and just do walks, easy swims, and easy strength. All were fine. She took a 2-week break from running and tried again on Day 36. Still abnormal increase.

Other symptoms were brain fog, impaired vision (one eye would be blurred), and dizziness.

Another week or so taking it really easy.

On day 47 she was able to increase the frequency of training but she kept the duration to about 60-75 minutes at low intensity (around Aerobic Threshold 65-75% of HRmax). Anything longer or harder and she would be out with a headache for solid two days.

We were able to check her heart with Echocardiogram to rule out a heart condition. An echocardiogram is in layman’s terms an ultrasound where soundwaves create an image of your heart. The cardiologist is able to see whether there are any abnormalities in your heart, such as enlargements, poor pumping function, clots in or around the heart, and whether the valves in your heart are functioning well. The doctor gave the green light to keep going.

It was clear she was suffering from long covid symptoms and would need to be really really patient with getting back to normal training. Racing an Ironman would have to wait for another year.

At the moment of writing this article in early June, Day 130 days of recovery. She has good weeks and then she has bad weeks where she is drained. She got the vaccine (Pfizer 3 weeks apart). Her response to vaccination #1 was a sore arm, while the second dose caused lethargy, body aches and chills, headache, and a very sore arm for 4 days.

On a positive note, she is able to perform at a high level, close to her pre-covid level in all disciplines, it is just that she needs to take more days off to recover than before and she still gets headaches that derail training. Her training volume and intensity have obviously dropped significantly and she is not anywhere near being able to accomplish longer racing like Ironman, but the trend of her progression is positive. We are feeling optimistic.

The second subject in the experiment of 2 (n=2), is anecdotal evidence of another female athlete, who was just about to race at her main race when she tested positive for Covid-19 back at the end of February.

Covid 19 Recovery and Following Vaccination Experience of a Female Nordic Skier In Her 20s

This athlete also recovered from Covid-19 itself really quickly, and she only had mild symptoms throughout, chills, headache, and nausea.

We monitored her heart rate and variability response closely. HR jumped initially from the low 60s to mid-90s (mean HR 69 pre-covid, 74 post-covid), while HRV decreased (pre HRV 8.0, post HRV 7.8), as expected. Otherwise, she was feeling good.

She followed the Gradual Return To Sports plan by Elliot et al. Where she lives, she was allowed to go outside for walks from day 1, which she did for her mental health. We monitored her HR and HRV which were elevated

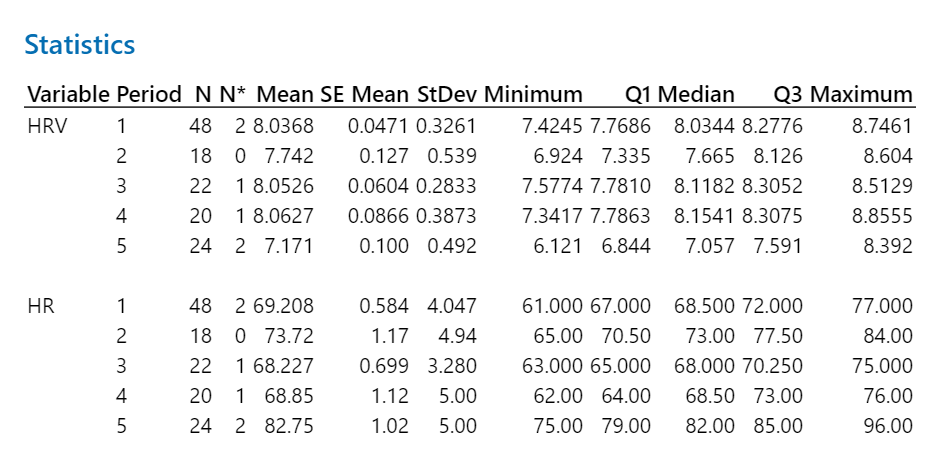

Period 1 = pre-covid (mean HR = 69.2, mean HRV = 8.0)

Period 2 = covid (mean HR = 73.7, mean HRV = 7.8)

However, the changes were small, and she felt great, so we decided to follow the GRTS plan from day 17 onwards, while always monitoring for symptoms. After GRTS completion we started her training with a conservative plan of 50-30-20-10% of normal volume while monitoring her HRV response. She was cruising through and everything looked like we were on track.

What happened next was totally unexpected and took us both by surprise.

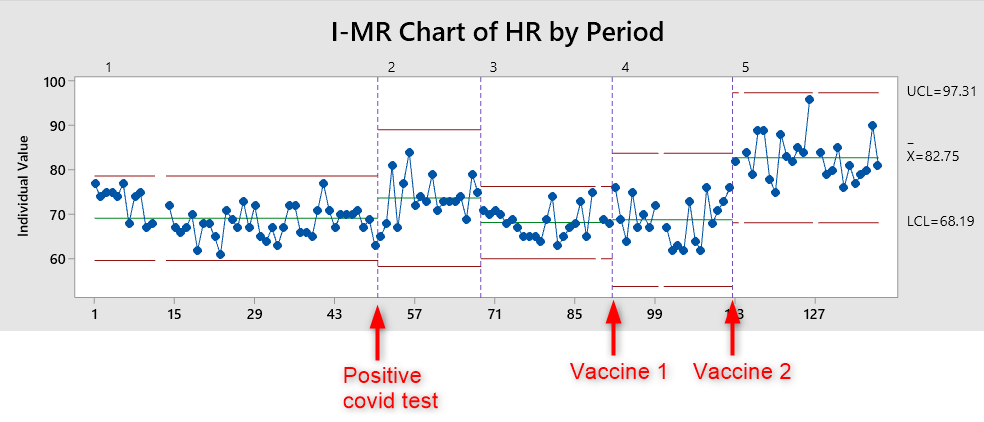

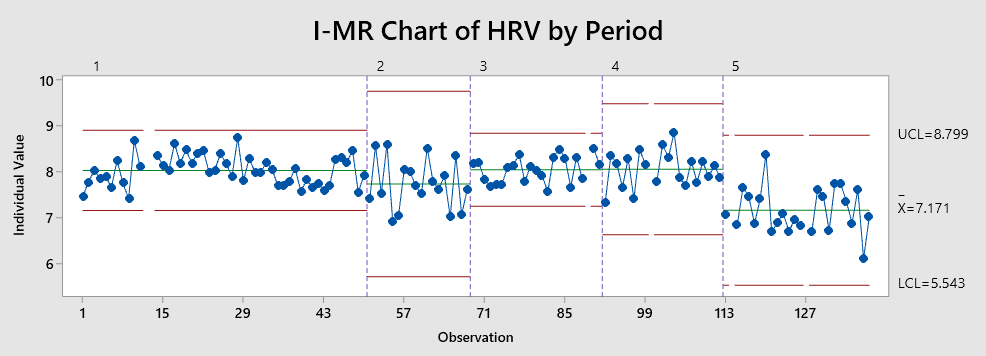

Take a look at the below charts and see if you notice it. Period 1 is pre-covid, period 2 is covid, period 3 is the return to training period before the first vaccine, and period 4 is the 3 week period between doses 1 and 2. Period 5 is post-vaccine dose 2.

Morning Heart Rate Response of a female endurance athlete in her late 20s pre-and-post covid and following vaccinations (3 weeks apart).

Morning Heart Rate Variability Response of a female endurance athlete in her late 20s pre-and-post covid and following vaccinations (3 weeks apart).

Statistic for HRV and HR for each period.

Did you catch it?

Her first vaccination came 2 months after covid. Her training was going great, her heart rate response had normalized to pre-covid levels. All good! phew! Or, that’s what we thought.

Yet, we were in for a surprise when after the second dose 3 weeks later, her HRV plummeted and HR jumped up. Some days it was over 90 bpm!

What to do but to jam on the breaks!

Throughout she said she was feeling ok. Occasional low-grade headache, but she had energy, and was eager to keep going. Alas, I am facing the most difficult task a coach has to do: hold the athlete back. Tell her she needs to take it easy. Like days completely off. Weekend off. We got her checked by her medical practitioner, who gave her the green light to continue training.

In medical terms, she may have gotten the green light as typically, morning hr below 100 is in medical terms, not a concern. But in practical terms for an athlete, a jump from the upper 60s to suddenly 90s IS a HUGE marker that something is off. It’s all about the perspective, I guess.

So what to do?

We take a long weekend off. HR goes down a little bit. I asked her to take more days really really easy. Like laughably easy. HR goes down a little bit again. We do this a few more days, and finally, after 5 weeks after the second dose, we are looking at HRV values back to pre-covid 19!!!!

It is incredibly hard to hold back an ambitious athlete who says she is feeling ok, yet, her HR response is beyond normal. It is incredibly frustrating for an athlete to see her hard-worked fitness decline (I wish we could just hide THAT CTL number on Trainingpeaks, am I right?!).

Remember, she is feeling ok, yet it is obvious her body is “going through stuff” and her BODY NEEDS rest more than it needs exercise. It is even more mentally challenging to see days go by and races that never happened when she is driven and feeling ready.

As I write this, we are finally at the point where we can start to think about building back again. It was a 15-week learning adventure.

As a coach, I’ve learned tons. Here are few key points:

- Trust your gut. When something seems off: hold the athlete back.

- HRV and morning HR monitoring is essential for the endurance athlete.

- Teach the athletes to listen to their body and when feeling off – it is better to take it easy than push it. Teach the athletes to trust in their own bodies. Because after all, they know their body the best!

The Risks of Increasing Exercise Too Early

You may be asking, how does this affect you and your athletes? The research shows that many people have post-covid fatigue syndrome, with a myriad of problems, such as headaches, fatigue, inability to hit higher intensities, and recovery that takes longer than “normal”. The true risk of pushing your athletes too hard too early is myocarditis, and whenever an athlete is forced to take a longer break, ligament sprains.

There is little advice for endurance athletes on how to take up their training and tackle the fatigue syndrome. So I decided to dig a little deeper.

Getting back too soon too hard can be really dangerous. We, endurance athletes, are often, how can I say this nicely…. well, incredibly driven and put our bodies through a lot. We love our sports and can’t wait to get back. Mentally we crave doing what we love. Sometimes we are a little too eager to get back into it while still recovering. With an infection still in our bodies, this can cause bigger problems than missing a few days off.

Here are some of the issues we may deal with if “pushing through” too early, too hard.

Myocarditis is an inflammation of the heart muscle. And it is a very real risk factor for even healthy, fit athletes who were not hospitalized during Covid-19. Myocarditis in the worst case can lead to sudden death. It also requires a complete stop of training for months. You really need to consider this as a possible outcome down the line if pushing too early, too hard, and while ignoring the symptoms.

Ligament sprains often happen when athletes start training again after a break. We as coaches need to remember to gradually increase the load, especially in sports that place a high demand on muscles and ligaments like ball sports and running. It is better to take a few more days or weeks easier and slowly build up distance and intensity back to where the athlete was prior than getting right back at it and be sidelined again.

So how exactly should you gradually increase your training as you clear the first phase?

I feel like the GRTS guidelines from phase 1 to 5 are temporally very short, especially for endurance and ultra-distance athletes like triathletes. Endurance athletes do a hell of a lot more than 60 mins a day, and weekly volumes are normally substantially higher. Many of us train 10-20 hrs per week, with regular 3-4 hrs per day. So how should we as coaches and athletes avoid any further complications as we slowly return to our training after Covid-19?

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) consensus guidelines for transition periods recommend a 50-30-20-10% approach as returning to training. To me, this makes sense. It is a gradual, 4-week increase of volume while monitoring for symptoms. The first week 50% of normal volume, then increasing weekly volume to 30% of the normal volume IF no adverse effects, like headaches, extreme fatigue, other symptoms like night sweats, insomnia. Then we add a little bit of workload until we are back to normal volumes. I would first increase volume while keeping intensity quite low. Think of it as another base building block.

Take it from someone who has had Covid, it is a different beast. It is NOT like the flu. I’ve never suffered from anything like this in my life! We still don’t know all the long-term effects of having covid, and certainly not how vaccination (and type or frequency of inoculation) affects athletes in training. It seems to affect different people differently, but one thing is certain. It CAN affect even fit, young people.

How Covid-19 vaccination can affect athletes

Again, we do not know the long-term effects of vaccination, and how they affect different athletes. There is no question in my mind that we all need to take our vaccination, but how we plan to take them (if we have any say in the matter) is a topic that I am really interested in.

An article by Hull et al (2021) in The Lancet points out that it may be beneficial to ease training immediately after the inoculation for 24-48 hr, especially after the second dose, which has been reported to cause more symptom than the first dose. Symptoms like local soreness in the arm which can last up to 5 days, headache, muscle soreness, and fatigue up to 7 days.

The same article mentions that athletes who are used to high frequency and intensity training may actually have enhanced vaccine response. Furthermore, the article refers to a study by Stenger et al (2020) which shows that exercise before the vaccination can also enhance vaccine response (to an influenza vaccine). Additionally, it seems the second dose tends to give more symptoms than the first dose.

So perhaps if the overall training plan allows, recovery days could be planned immediately post-vaccination.

When it comes to the n=2 of this article, the younger athlete reacted to the second dose more than to the first one, while the older athlete only reported soreness in the arm to the first dose. The older female athlete reacted to the second dose more with headache, chills, fatigue the day after, and more soreness in the arm that lasted 4 days. She took 4 days off after the vaccination as she was not feeling great. Her HR elevated by 10 beats and HRV decreased initially the day after the vaccination but returned to normal after 3 days.

As we learn more about the effects of vaccinations, we need to monitor the athlete’s symptoms and HRV response closely and let the body do its wonderful job of building antibodies and enhance the immune response. Allowing the athlete’s body what it needs with proper nutrition, rest, and high-quality sleep may be all it needs to bounce forward.

What should you monitor in your athlete post-covid and around vaccinations?

How can we as coaches monitor athletes as they are going through the gradual return to training, and after the vaccinations? Monitor HR and HRV response by asking your athlete to either share screenshots from their HRV app (if you don’t have a coach version of the app in which case you can already see your athlete’s data), and subjective scores like how they are feeling, how is their sleep, overall energy, etc. Also, make sure to teach the athlete to monitor any symptoms like;

- Chest pain or heart palpitations

- Nausea

- Headache

- High heart rate not proportional to exertion level or prolonged heart rate recovery (both acute under training and after training

- Feeling lightheaded or dizzy

- Shortness of breath, difficulty catching breath, or abnormal, rapid breathing

- An excessive level of fatigue (is your athlete crashing during the day?) for an athlete who is used to napping during the day, might be apparent by longer sleep or feeling fatigued even after the nap

- Swelling in the extremities

- Passing out

- Experiencing tunnel vision or loss of vision

- In addition, abnormal HR and HRV response.

Modified from https://health.clevelandclinic.org/returning-to-sports-or-exercise-after-recovering-from-covid-19/.

Your athlete could have one or two of these symptoms or all. The older athlete in our experiment of n=2 had all these symptoms during the recovery while at the same time her HRV returned to normal within 5 days after the positive test result. You may just have to go with your gut feeling and lean on the conservative side when evaluating whether the athlete is ready to return.

What about the fact that you have an ambitious, eager athlete in your hands who wants to get back to training, and/or is worried about losing fitness. If you are using Trainingpeaks or any other training platform that uses training data to estimate the athlete’s fitness, you know how addicted your athletes can be to monitor this one number daily…

Don’t overlook the anxiety about losing fitness, but don’t overestimate the detraining effect either

Talk with your athlete often, and talk about the fact that she/he is in fact in detraining. Do make sure to ensure that she/he is not losing as much fitness as she thinks she is. It can be useful to recommend using meditation if the athlete is feeling very anxious to get back to training, or fear of losing fitness, or fear of losing racing opportunities. It is a tough period, but there is light!

It’s important to understand, that despite the illness and long gradual return to training (which is necessary even for the fittest athletes!), she or he is NOT losing as much fitness as she may think! Listen to this podcast episode by Ross Tucker on the Science of Sport about Fitness Adaptation and Reversibility here

It is a really interesting and positive listen for any coach or athlete. They show a few studies that indicate that detraining effect varies about 2-4% per week (decrease in Vo2max, Power output, red blood cell count, hemoglobin, Workload at Lactate threshold, etc) detraining in elite athletes. Although this number will possibly be a bit higher for non-elite athletes or people who do not have 5-15 years of regular training under them, it is really encouraging. But that is not the only good news.

The good news is that you can actually cut your losses.

The studies show that even 1/5 of your normal training can cut your fitness losses by half!

Let that sink in.

So let’s say our athlete #1 trains 10hr per week, and due to illness, family vacation, covid, etc. she needs to reduce training to 2 hr per week. She can defend against the loss of fitness by half just by doing a specific bout of training as little as 30 mins 5 days a week, or even two 60 mins runs/rides, etc! There is also a specificity principle of biological adaptation that must be taken into account with detraining. For example, in a case where a runner goes on a family vacation, or work obligations take over, a simple 30 min high-intensity session once a week can prevent detraining effects on high-intensity performance, i.e. 5K race performance (Houmard et al, 1990). That is quite incredible!

What about re-training then?

How fast can you expect to be “back”? Well, this may actually be a different situation when it comes to COVID-19, especially if you have long symptoms. But, as Tucker mentions you can expect to regain the fitness half the time you de-trained. For example, detraining period 4 weeks, and you can regain the fitness lost in 2 weeks (more research needed for females and young people endless trained people).

With long covid-19 sufferers, this may be somewhat frustrating, as we know it will take a lot longer because some days you feel like you just got hit by a train and you cannot recover no matter what you do. So it is more like a “normal” injury recovery where you take a few steps forward only to take several more steps back. It is never a linear line of progression, and I believe this is very important to keep in mind for coaches and athletes.

So if we focus on the positives, athletes are not going to lose as much as they think, they can defend against the losses by training very little, and they can regain it a lot quicker than they think. Also, sometimes when an athlete has trained hard and gets sick, the forced downtime may actually be beneficial for her and allow her to come back healthier, stronger and fresher both mentally and physically.

There is no reason to panic!

Anxiety

When it comes to our n=2 experiment, the older athlete’s performance is close to pre-covid levels despite over 100 days of less volume, less intensity, and definitely less specificity of Ironman training. In her specific case, it seems as if this “forced period of less” has not been as detrimental as she may have thought.

I do want to emphasize the need to recognize the athlete’s anxiety and worry about losing fitness. As coaches, we need to be empathetic about the athlete’s feeling of anxiety and worry and address the issue. Stress is stress and your body doesn’t differentiate the source of stress. Finding a way to carefully acknowledge the topic of detraining, informing the athlete about studies about detraining can help the athlete to trust that it is not as bad as it may feel.

I sincerely hope this article will help you as a coach or an athlete as we all navigate through these challenging times of Covid-19 recovery. Please feel free to share this article with anyone you think needs reassurance that not all is lost.

PS. For transparency, the older female athlete in this article is yours truly. The other athlete remains anonymous.

Be Sisu Fit – Endurance Sports Coaching

Sources:

Caterisano, Anthony Co-Chair1; Decker, Donald Co-Chair2; Snyder, Ben Co-Chair1; Feigenbaum, Matt1; Glass, Rob3; House, Paul4; Sharp, Carwyn5; Waller, Michael6; Witherspoon, Zach2 CSCCa and NSCA Joint Consensus Guidelines for Transition Periods: Safe Return to Training Following Inactivity, Strength and Conditioning Journal: June 2019 - Volume 41 - Issue 3 - p 1-23 Ibarrola, M., & Dávolos, I. (2020). Myocarditis in athletes after COVID-19 infection: The heart is not the only place to screen. Sports Medicine and Health Science, 2(3), 172–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhs.2020.09.002 , et al. Infographic. Graduated return to play guidance following COVID-19 infection.

Hull J, Schwellnus MP, Pyne DB, Shah A. COVID-19 vaccination in athletes: ready, set, go… The Lancet, Vol9, Issue 5, P455-456, MAY 01, 2021 Timing of Vaccination after Training: Immune Response and Side Effects in Athletes

STENGER, TANJA1; LEDO, ALEXANDRA2; ZILLER, CLEMENS1; SCHUB, DAVID2; SCHMIDT, TINA2;

ENDERS, MARTIN3; GÄRTNER, BARBARA C.4; SESTER, MARTINA2; MEYER, TIM1

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise:July 2020; volume 52;7; 1603-1609

Websites: